Increasing role of nested services in crypto fraud

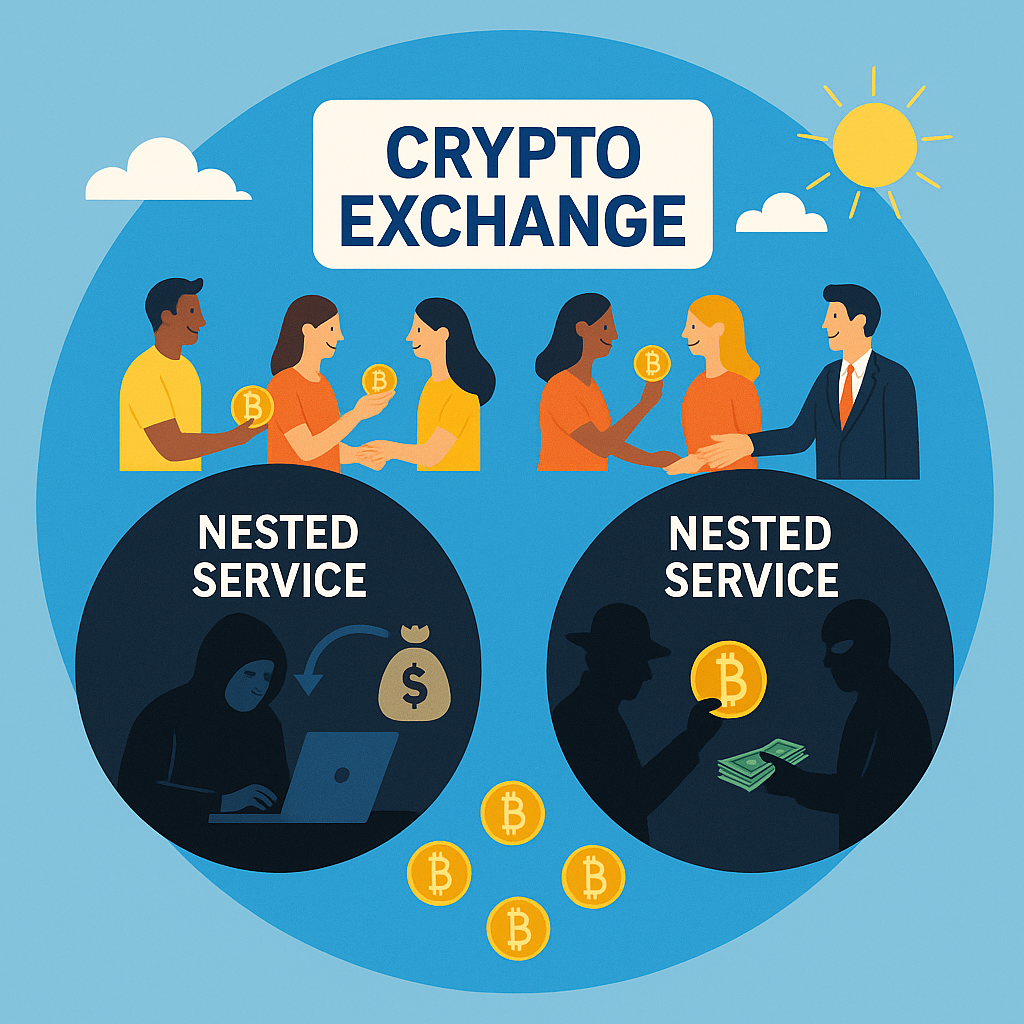

In recent crypto fraud cases, we observe a clear trend: nested services play an increasingly prominent role in trading crypto assets obtained from fraud. These services receive crypto currency from fraudsters, sell it through accounts on major exchanges to bona fide third parties, and then distribute the proceeds to a hidden user of the nested service. These users remain out of view to the exchange on which actual trading takes place. This mechanism makes detecting and blocking criminal money flows extremely complex.

At the same time, several lawsuits are now pending – both nationally and internationally – focusing on, among other things, whether wallets of nested services can be frozen. Those lawsuits are crucial to clarify the legal scope of measures against these constructs.

Based on information from ongoing fraud investigations, we believe it is necessary for regulated crypto-exchanges to cease providing nested services and freeze assets if requested. Otherwise, KYC and AML obligations are easily circumvented, creating a parallel financial system where anonymity and money laundering go hand in hand.

What are nested services?

A nested service is an intermediary that opens a trading account with a regulated exchange, and provides third-party access to crypto trading through that account. Unlike the main exchange, the nested service typically hardly performs KYC (Know Your Customer) or AML (Anti-Money Laundering), which makes its use attractive to rogue actors.

Thus, in practice, a service provider is nested within a regulated platform without itself complying with the associated regulations. The large exchange sees only one customer – the nested service’s account – and therefore has no visibility into the underlying transactions and users.

The legal battle: can wallets of nested services be frozen?

The legal debate over the freezing of wallets operated by nested services is in full swing. In the Netherlands, several courts have confirmed that freezing orders and/or crypto preservation orders are possible at a cryptoexchange. However, if nested services use shared wallets or multiparty computation technology, it becomes virtually impossible to track and legally detain individual assets. Principal cryptoexchanges sometimes take the position that freezing is not possible because (from their perspective) assets are untraceable (the nested service can link the assets to individual users, however). The irony is that victims of fraud and their lawyers who base lawsuits on blockchain tracing research cannot see on the front end that they are dealing with a nested service, so court orders freezing wallets can target wallets that later turn out to be from a nested service. The main exchange then still faces an order to freeze the wallet. The main exchange then usually takes no chances and respects the freezing order, even though it was a nested service. Such a judgment with a freezing order is sometimes necessary to make the nested service fall through the basket of the main exchange, which apparently turned a blind eye or had not been paying close attention but did consider, after reviewing the reported fraud, that nested service activities are undesirable. The effect is then to freeze all assets.

Another fundamental question is to what extent a nested service can itself be held responsible for the financial damages resulting from fraud. This is particularly relevant when it is clear that the service provider has created the conditions that facilitate fraud and money laundering.

The hidden user: the money mule as a switching point

In practice, the “customer” of a nested service almost always turns out to be a so-called money mule: someone who – knowingly or unknowingly – makes their identity or wallet available to a cybercriminal organization. These are often financially vulnerable individuals who have little awareness of the legal consequences.

Through a blockchain address controlled by the cybercriminal, the proceeds of the fraud, after selling the stolen cryptocurrency through the main exchange, enter the money mule’s account with the nested service. The amounts involved range from tens of thousands to many millions of euros per fraud – totaling many billions when you add up all the damages. For victims of fraud, it is not impossible to find the money mules, but this requires a lot of effort: first a procedure against the main exchange to find out the name and address of the nested service and then a second procedure against the nested service to find out the name and address of the money mule. Once these legal hurdles are overcome, it often turns out that it is still not possible to recover damages from the money mules: money mules are often untraceable or have no recourse at all, and the nested service have accounts emptied. Nested services rarely freeze suspicious assets. This makes sense: they serve a special client group, fraudsters looking to launder loot. We also see in practice that the names and addresses of the money mules known to the nested service are sometimes incorrect – and apparently not verified. It is the cybercriminals who actually cash out. In some cases, millions have disappeared but the money mule has nothing.

Nested services as magnet for organized crime

The lack of decent KYC and transaction monitoring makes nested services particularly attractive to fraudsters seeking to conceal their identities. It is therefore defensible – and in some cases plausible – that many nested services have been established with the primary goal of facilitating anonymous, untraceable money flows.

These rogue players in the crypto world thus target a specific audience: perpetrators of fraud, cyber criminals, money launderers and other members of organized crime, who are looking for a reliable way to cash out criminal proceeds without visibility to investigative agencies or financial regulators. It is obvious that the fees charged by nested services to their special customers are a lot higher than the fees charged by cryptoexchanges to consumers for normal cryptocurrency trading. After all, the owners of nested services are at risk of police and judicial attention.

Small and large

There are small, medium and large nested services. Most notable are the small ones. They make little effort to appear as legitimate businesses. They have no website, the business is sometimes in the name of a “cat-catcher” and actually controlled by others, and they are not licensed. These companies are clearly empty shells set up to collect stolen money in the form of crypto. With the medium-sized variety, the picture is a bit more complicated. Sometimes there is a website that suggests normal activities of a cryptoexchange, but it does not appear to be possible to become a customer and no contact with a help desk is possible. The website then appears to be inactive and a front. There are also very large nested exchanges that are openly active in the consumer market with a functioning website. Their contention is that they can offer customers better selling prices because the purchase of cryptocurrency is done through the main exchange that handles more volume. That seems like a legitimate goal, yet it is noteworthy that blockchain investigations show that such a large exchange also receives large numbers of cryptocurrencies from fraud, purchased by the victims from another exchange, which fall into the hands of criminal organizations through, for example, boiler room fraud (or “pig butchering”), which are sold to unsuspecting customers of the main exchange, after which the proceeds go to money mules used by the cybercriminals. The impression with these large, openly active nested services is that a separate branch with money laundering activities on behalf of fraudsters has essentially been set up or is being allowed to operate in addition to providing services to consumers.

Civil liability: service providers with a money laundering purpose?

When a service provider structurally fails to comply with KYC or AML obligations while in practice facilitating fraudsters to anonymize and move their proceeds, civil liability is not only defensible but necessary.

The social duty of care entails that such service providers can be held liable for the harm they help facilitate. In legal terms, a tort occurs if the business model is essentially aimed at facilitating money laundering – a model that appears to serve no purpose other than to create an anonymous money laundering trail.

Conclusion

Nested services pose a structural risk to victims of cryptofraud, the integrity of the financial system and the enforceability of regulations. They operate as links in a shadow infrastructure in which perpetrators make themselves invisible, victims lose their money and detection becomes bogged down. Service providers who knowingly or through gross negligence maintain such structures must be held accountable under civil law. This is the only way to rebalance the playing field and give victims the prospect of recovering their losses. The future will reveal how judges judge the activities of nested services.