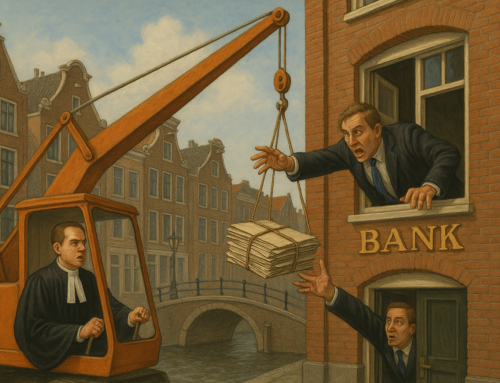

ING has been fined by the Public Prosecution Service because the bank does not act properly against money launderers. Criminals who transfer money through ING are not dealt with properly by the bank.

There are many developments in the field of money laundering, mainly due to new technological possibilities. De Nederlandsche Bank (DNB) not only supervises the stability, but – in keeping with the spirit of the times – also the integrity of the financial sector. Trust offices can have a say in this: the rules have been tightened up so much that you would almost think that the sector is undesirable.

Transaction monitoring is “hot”

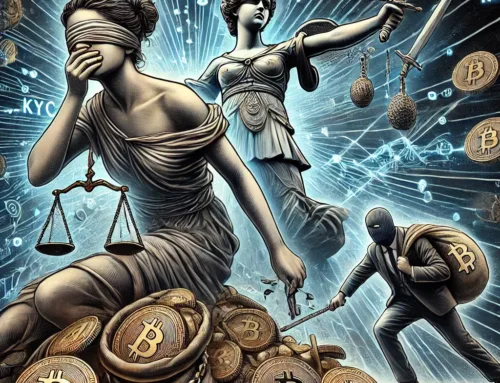

One of the most interesting developments can be found in “transaction monitoring”, which mainly concerns banks and payment institutions. Transaction monitoring is not new, by the way, and is the logical follow-up to the assessment when taking on new customers. DNB expects financial institutions to refuse customers with dubious objectives. But the intentions of new customers are not always clear: you only know later what the customer is going to use the account for. Scammers and semi-scammers from all backgrounds need a checking account to run their business. Think of boiler rooms that want to receive “investments”, high-tech fraudsters such as hackers who prey on ransom, and organizers of pyramid schemes. The true intention of these criminals will become clear to an observant financial institution after a while, while the victims are still sleeping peacefully – they still lack insight into the movements in the account. Consider the situation that the account of a newly established BV receives high turnovers that are paid directly to an account abroad. Such a flow of money can (in retrospect) be part of a fraud scheme and come from the brain of a criminal.

Red flags

DNB’s idea is that algorithms that detect unusual or remarkable transactions on accounts should alert the banks. A legal obligation to intervene in the criminal money flow of the customer to protect victims is then not far away. Of course, making such far-reaching decisions remains human work, but technology will provide increasingly sophisticated “red flags”. In the meantime, criminals are also getting smarter. Transferring money directly from the Netherlands to the Ukraine is not very convenient, but if it runs through intermediate stations in Central Europe, it becomes more difficult for a Dutch bank to spot anything suspicious in the money flow, depending on what you mean by “usual”. The increased standards imposed by the regulator on the financial sector are grist to the mill for lawyers who provide legal aid to victims of fraud and deception. A duty of care applies to banks. The first association with the word duty of care is: take good care of your own clients. But the duty of care goes further. According to the case law of the Supreme Court (HR December 23, 2005, NJ 2006, 289) banks also have a duty of care towards third parties. This also applies to victims of a boiler room, who are tempted to deposit their investment into a checking account at a bank where they do not have an account themselves.

More lawsuits?

You can now guess what will play out in the courtroom in the future. The bank that does not technically have its transaction monitoring in order and that allows itself to be used by criminals will get wet. And not just because the Public Prosecution Service is acting harshly, as it is at ING. The bank that does not set up a control tower with flesh-and-blood bankers who block money flows after a report from the system can count on claims for damages. That an account is being used for criminal purposes is suddenly no longer a matter of hindsight, but a fact that the bank should have recognized on the basis of its technological knowledge. And that at an early stage, when the transactions can still be blocked. Financial criminals are very good at funneling money to sunny mailbox islands: there is little to gain for victims there. It is different with a bank that senses the trend too late. Hard euros can be obtained from the banks if they commit a wrongful act against their own clients or third parties because they do not have their transaction monitoring in order. The fine that ING received from the Public Prosecution Service is grist to the mill of defrauded individuals and companies against the banks. The first lawsuits are already underway and my impression is that the banks still have to get used to the developments.

ING against Foot Locker: success for fraud victims

The importance of transaction monitoring is now also permeating published case law (many settlements are made with secrecy because banks do not like negative publicity). ING was sentenced in 2017 in the Footlocker case to pay compensation in a fraud case. Footlocker was the victim of a scam perpetrated by an ING customer. The bank reacted much too slowly and clumsily to the unusual transactions. Read the article about this case here . ING has also lodged an appeal; the case law is still being developed, but the fine that ING has meanwhile received does not bode well for the bank.

Fine

The fine that ING received from the Public Prosecution Service is based on the fact that ING does not act properly against money launderers. The Public Prosecution Service has established, among other things, that the bank’s application of transaction monitoring is too limited. The fine strengthens the legal position of victims of fraud committed by criminals with an account with ING Bank in civil lawsuits. The big question is whether other banks have their processes in better order. Our impression is not. Our office is – coincidentally perhaps – pending several cases, but not against ING at the moment….

Published by Marius Hupkes