Banks must know their customers and sell appropriate financial products. The word ‘duty of care’ therefore primarily refers to clients who buy investment products from the bank, and to account holders. However, a bank’s duty of care goes further: banks also have a duty of care towards third parties who are not customers or investors of the bank.

Basis in law

The duty of care of banks towards third parties finds its legal basis in art. 6:162 BW, a key article in the Civil Code. A bank that violates its duty of care towards third parties is acting unlawfully and can be ordered by the court to compensate the damage suffered by the third party. If the bank breaches the duty of care towards its own clients, the legal basis is attributable shortcoming (non-performance), unless the breach of the duty of care took place before the contractual relationship with the client arose. For example, you can think of providing incorrect information about the characteristics of an investment product before purchasing.

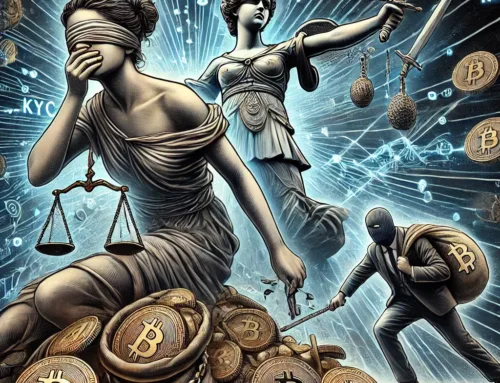

The “Safe Haven” Statement

On December 23, 2005, the highest court in the Netherlands rendered an important ruling on the duty of care of banks towards third parties (HR December 23, 2005, NJ 2006/289, ECLI:NL:HR:2005:HU3713 ). The Supreme Court gives the following formulation of the duty of care that banks have towards third parties: “The social function of a bank entails that there is a special duty of care towards third parties whose interests it should take into account on the basis of what is customary in society under unwritten law.”

open standard

According to the Board, the scope of this duty of care depends on the circumstances of the case: it concerns a so-called ‘open standard.’ In legal practice, this means that a victim will have to submit a case to the court if the bank does not recognize liability for compensation, after which the court determines whether the bank has breached its duty of care in the relevant case. In the case that led to the Safe Haven judgment, investors (who were not customers of the bank in question) were duped by an institution that was operating without a license. This institution collected the deposit via an account with the bank. The deposit disappeared and there was nothing left to get. As a result, the victims were critical of what the bank had played in this. A crucial point in the ruling was that the bank had offered the current account when it should have known that its customer did not have a license.

An investment fraud in Hilversum

In 2015, the Supreme Court once again made an important decision on the duty of care towards third parties (NJ 2016/245, ECLI:NL:HR:2015:3399 ). This time, the Supreme Court tightens up the wording with regard to offering payment facilities to scammers. The high Council: “The social function is related to the fact that banks play a central role in payment and settlement systems and services in this area, are pre-eminently experts in those areas and have access to information that others lack. The position justifies that the bank’s duty of care also serves to protect against frivolity and lack of expertise and is not limited to care towards persons who have a contractual relationship with the bank as customers.†

What was this case about?

The bank’s wrong customer had opened accounts at a branch in Hilversum. The bank’s customer became involved in a so-called Ponzi scam, a form of investment fraud in which fake returns are made. Deposits from old customers are repaid with contributions from new customers and in the meantime the fraudster diverts a significant part of the deposit to foreign accounts or assets in the name of others. What exactly did the bank do wrong in this case? What it comes down to is that the judge looks at the knowledge that the bank branch must have had about the fraudster’s business and conduct. The judge accused the bank that the bank must have known for a long time that there was fraud even though no action had been taken. Ultimately, the bank had to pay for the damage.

Complete view

Incidentally, the victims in this case had united themselves in a foundation and as a result, information about the incoming and outgoing movements on the account ended up in the procedure. That is not information that the bank would be happy to provide information about on its own initiative. The victims in these kinds of cases can provide information about the deposits themselves, but the outflow naturally forms a blind spot for them, but a great deal had also become known about this during the proceedings, namely through information from the trustee in bankruptcy of the fraudster. and by the indictment (plea) of the public prosecutor, who prosecuted the swindler. Because of these sources of information, the civil court had a complete picture of the changes in the bank accounts and thus the judge was able to conclude that the bank had been too lax and had violated the duty of care. That is often the crux of these kinds of lawsuits. If a lot of money comes in and the account holder immediately transfers everything abroad, while the bank does not intervene, the criterion for liability is quickly met.

Transaction monitoring

Since the Safe Haven judgment, it has become more common for victims of fraud in various variants to accuse the perpetrator’s bank of a breach of the duty of care. A duty of care claim can be brought by a third party against the bank in all cases of fraud, fraud or fraud in which the perpetrator collects (investment) money and does not actually invest it, but makes it disappear. The case law of the Supreme Court forces the banks to take a critical look at their own customer base. This applies in the phase in which the customer opens an account, but it also applies if the customer is going to use the account: the bank is expected to watch. The technical tool for this is transaction monitoring . The bottom line is that banks cannot act as passive facilitators of fraud, scams and scams, they run the risk of being accused by the judge of letting things take their course. These checks that banks have to constantly apply to their own customer base are of course not easy. Sophisticated fraudsters start a legal business or combine fraud with transactions that are legal. But the bar is set high for the banks and that gives victims an important starting point for addressing the bank if the antenna was adjusted too roughly or in certain cases is not switched on for a while.

Developments in the judiciary

It is not self-evident that judges of banks expect that the movements on the account of wrong customers will be monitored. This is apparent from, for example, a somewhat older judgment (in Dutch) in a procedure against ING bank from 2008. The court considers: “ING states that changes in its customers’ accounts are processed and administered via almost fully automated systems. Even if the transactions were known to it, it still had no reason to regard them as irregular. The court is of the opinion that ING’s defense is successful. As a bank, it has to process such a large number of transactions that it cannot be required to delve into the background of each of the transfers that take place from or to the accounts it administers.† In fact, the court here says that the bank does not have to apply transaction monitoring. It is highly questionable whether this argument can still benefit a bank 10 years later. The regulator, DNB, has made it clear in detailed regulations that a bank should in fact delve into the background of the transfers. The central bank has tightened the standards considerably. It is obvious that the procedure from 2008 would now turn out differently.

Turning point: Footlocker/ING Bank

The fact that the judiciary now sets higher requirements for banks is apparent from a judgment of 26 July 2017 by the Amsterdam District Court. The facts are as follows. A 25-year-old man registers a sole proprietorship with the Chamber of Commerce. He opens a business account with ING. Through invoice fraud he cheats Footlocker, a large company, almost € 2,000,000. The money disappears and the man is criminally convicted. Footlocker appeals to ING to compensate the damage due to a breach of the duty of care (Safe Haven). ING must defend itself. ING also appears to have found the transactions strange. A report has been made to FIU-the Netherlands. A questionnaire was also sent to the account holder. He first responds with an excuse (vacation) and then he gives false answers (he would receive a commission from Footlocker). The court blames ING for this lax approach. The account holder could have simply been called immediately to give an explanation and the account should have been blocked to limit the damage. ING must compensate the damage, less a percentage of its own fault due to carelessness (Article 6:101 of the Dutch Civil Code). And the criminal account holder of ING? Well, he has cleverly channeled the money away. There is nothing more to gain from him. He can lead a lazy life after serving his sentence.

Conclusion

Banks’ duty of care does not only concern matters in which the bank is liable to customers. It could also be the situation where the bank is approached by victims of a scam where the bank has been used by the scammer to receive and transfer money. In this situation, the bank itself is also a victim of the fraudster , but the bank can nevertheless be liable if it handled suspicious payment transactions too lax and the internal alarm systems failed. That is the consequence of the case law of our highest court, which is of the opinion that knowledge that the bank has or may have (about diversion, money laundering and suspicious transactions) must also be used to prevent damage.

Published by Marius Hupkes